Dr. Peter Berger: ‘Biodiversity depends on cultural diversity’

Peter Berger, Associate Professor of Indian Religions and the Anthropology of Religion at our Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, and René Cappers, archaeobotanist at the University of Groningen’s Faculty of Arts and Professor by special appointment of Ecology and Palaeo-Ecology of the Near East at Leiden University, are extremely pleased with not just one, but three(!) fundings of three interconnected and interdisciplinary research projects on millets, rice and wheat in South and Central Asia.

NWO and DFG grants for three projects

Not only the Dutch Research Council (NWO) funded the research project of Dr. Peter Berger in cooperation with Prof. Dr. René Cappers and the German Prof. Dr. Roland Hardenberg from the Frobenius Institute for Research in Cultural Anthropology (Goethe University, Frankfurt). Two other, yet interconnected, projects in which these three scientists cooperate had previously been funded: Roland Hardenberg successfully applied for their funding by the German Research Foundation (DFG). The good news about the NWO grant for Peter Berger’s ‘Salvage crops, “savage” people: A comparative anthropological and archaeobotanical investigation of millet assemblages in India’ followed 1,5 months ago.

Cooperation between The Netherlands and Germany

Peter Berger: ‘In March 2017 Roland Hardenberg and I were on a retreat on Schiermonnikoog and thought about the project we would like to develop. We wanted it to be a cooperation between Germany and The Netherlands, but found out that there were apparently no collaborations between NWO and the German research foundation DFG. Therefore we both wrote an application for two complimentary projects on millets in India. We prepared the proposal very thoroughly: we had an expert meeting in London – where I first heard about my RUG colleague René Cappers, and found out that he is the expert we had been looking for! –, we had conferences, publications, workshops, and René and I went to India together for pilot research in 2019. And then something happened that we did not expect: we got two grants! So now we can start both projects, and even a third one – on rice in India and wheat in Kazakhstan – together with another colleague, Dr. Jeanine Dagyeli.’

‘We didn’t get a single negative review!’

Peter, could you tell us about more about the actual course of such a comprehensive research funding application like the one you did for the NWO Open Competition…? ‘Sure! We submitted three proposals to NWO. In January 2020 we submitted an initial proposal, of just five pages or so. Then the NWO selected more than hundred proposals and we were invited to write the full proposal. We spent much of the summer of 2020 working on that and had meetings with our colleagues in Germany and here. Then we submitted the full proposal in September 2020 after which the NWO sent it to various experts, who reviewed it. Once we received the reviews of the specialists, René and I had a week to write a “rebuttal” to their comments, of max. 2 pages. When you read the reviews that we got on the project it’s actually flabbergasting; we really ticked all the boxes and didn’t get any negative reviews! At the end of April 2021 NWO informed us that we had been awarded a €750.000 grant.’

Magic grain

‘In our projects the interdisciplinary work, the collaboration between anthropologists and biologists, is very important. And the relevance of this project is much broader than “just” India,’ Berger explains. ‘The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the United Nations were also discussed. The year 2023 has even been declared the International Year of Millets by the UN, because the global community of scientists was convinced that millet actually is a magic grain! It doesn’t need much water, it has high nutritious value, it’s very strong, easy to cultivate, pest resistant, gluten-free, climate friendly, etcetera. Millets is therefore regarded as a magic kind of crop that will solve all kinds of problems in the future globally, so there is a general interest in promoting that grain.’

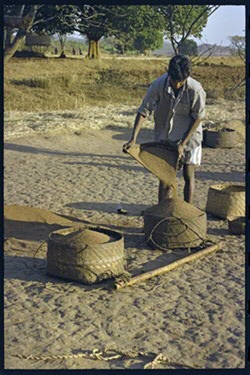

‘The paradox is, however, that the highland communities in Central India, who have been traditional millet cultivators for ages, have always been looked down upon by the Indian government and by the mainstream society as “backward”, “uneducated”, “primitive” and “savage”. And all of a sudden, millet is regarded a “salvage” crop! The main aim of our research proposal was to tackle that paradox, indicated by the title Salvage crops, “savage” people. People now slowly realize that these indigenous peoples know a lot and that we could profit from this also globally. So another (societal) aim of the project is to provide a space for these different stakeholders to communicate with each other and to bridge the gap between these different (food) worldviews.’

‘Crowning glory of my work’

René Cappers elaborates on this: ‘It is of great value that, by this project, we can contribute to the acknowledgement of the knowledge and skills of these traditional agricultural communities. It has been my long-cherished wish – as a biologist/archaeobotanist who studies subfossil plant remains – to cooperate with anthropologists, as this enables us to much better understand the different aspects of crop selection both today and in the past. The NWO remuneration makes this cooperation possible.’ Professor Cappers (born in 1957) adds: ‘This will probably be one of the last projects I will be involved in, so it’s a bit like the crowning glory of my work. I’m very happy that my career can be completed with this cooperative research on millet (cultivation and crop selection) improvements.’

Sustainability needs biodiversity and cultural diversity

Dr. Peter Berger: ‘The governments have in mind food security, but biodiversity comes along with cultural diversity. That is actually one of our main arguments. You need the knowledge and skills of these indigenous people but it is also utterly important to understand how these grains are embedded culturally. For these communities these grains are not only nutrition, but they have religious value as well. Government policies will only be sustainable if the worldview, the culture of the people, is taken into account. We hope that this project will, on the one hand, challenge the degradation and discrimination of these local communities. On the other hand, there will be a benefit for the government and the policies, because a better mutual understanding will also make a success of those policies more likely.’

Highly competitive

With the NWO-funding the 4-year project can now actually start. Peter and René are currently looking for two PhD positions in the field of Anthropology, and a postdoc in the field of Archaeobotany, to get the project fully started by November/December 2021. How important is this achievement for the GGW and the Arts faculty? ‘Having such research projects is crucial for any faculty in any university. You should know that calls like NWO’s Open Competition are highly competitive. Receiving the funding shows that our faculties have good research ideas and that we do relevant research that’s worth spending taxpayers’ money on. We do this both for society at large and the students, as the PhD-students and postdocs whom we will train and hire for this project are the professors of tomorrow, we hope. This NWO grant is not just a great scientific reward, but also in terms of money, and renown,’ Peter Berger concludes.